Tolstoy on the Importance of Books and Literacy in Prisons

“When you are free you don’t have such a painful desire to read as you have in prison. You can get any book at home, in the shops or from the internet. In prison books become the air. Your body needs air to breathe. No books – you cannot breathe. And if you cannot breathe there is no life.”

– Belarusian journalist Iryna Khalip, who was detained for criticising her country’s regime, now contributing to the campaign against banning books in UK prisons

|

| Leo Tolstoy, an author committed to education and literacy for all, would certainly condemn the UK restrictions on prisoners receiving books. |

Over the last few months, countless artists, writers and readers have spoken out against ‘book bans’ in UK prisons. New rules, which came into force last November, now prevent prisoners from receiving parcels from outside, including books and magazine subscriptions, unless for ‘exceptional circumstances’.

In an article by The Guardian, one prisoner, who was about to start a distance learning course, states: “A friend of mine has done all these courses and is fully qualified and was going to send me all his books but we can’t have books sent in any more.”

When thinking about this unfathomable decision by the British prison system, Resurrection by Leo Tolstoy can be seen as key reading.

It’s perhaps not a surprise that Tolstoy believed firmly in the redemptive qualities of reading for prisoners, what with the school he set up on Yasnaya Polyana, his estate, in order to increase literacy among peasants, and the work he did to reform Russian education and literacy rates.

The protagonist of Resurrection, Nekhlyudov, a character keen to find redemption by helping others, is forbidden from giving textbooks to a political prisoner for the sake of furthering his education. In protest, his argument with the prison general goes as follows:

‘He needs textbooks. He wants to study.’

‘Don’t you believe it.’ The general paused. ‘They’re not for studying. This is trouble-making.’

‘But surely they need something to pass the time in their awful situation,’ said Nekhlyudov.

‘They never stop complaining. […] They have comforts here that are not usually available in prisons.’

The general goes on to say by way of an excuse,

‘They are given books with a spiritual content, and old periodicals. We have a library of suitable books. But they don’t read much. At first they show some sort of interest, but very soon you’ll find new books with half the pages uncut, and old ones with the pages unturned. We once ran a test,’ said the general with something distantly resembling a smile, ‘by inserting slips of paper. They never got moved. […] Anyway, they soon settle down. They start off by being a bit restless, but it’s not long before they’re putting on weight, and they end up quite placid,’ said the general, totally unaware of the sinister significance of his words.

Tolstoy wasn’t the only author aware of the importance of books in prisons. Think of the well-read Abbé Faria in The Count of Monte Cristo, one of the greatest mentors in literature, who writes his masterwork, the Treatise on the Prospects for a General Monarchy in Italy, while imprisoned.

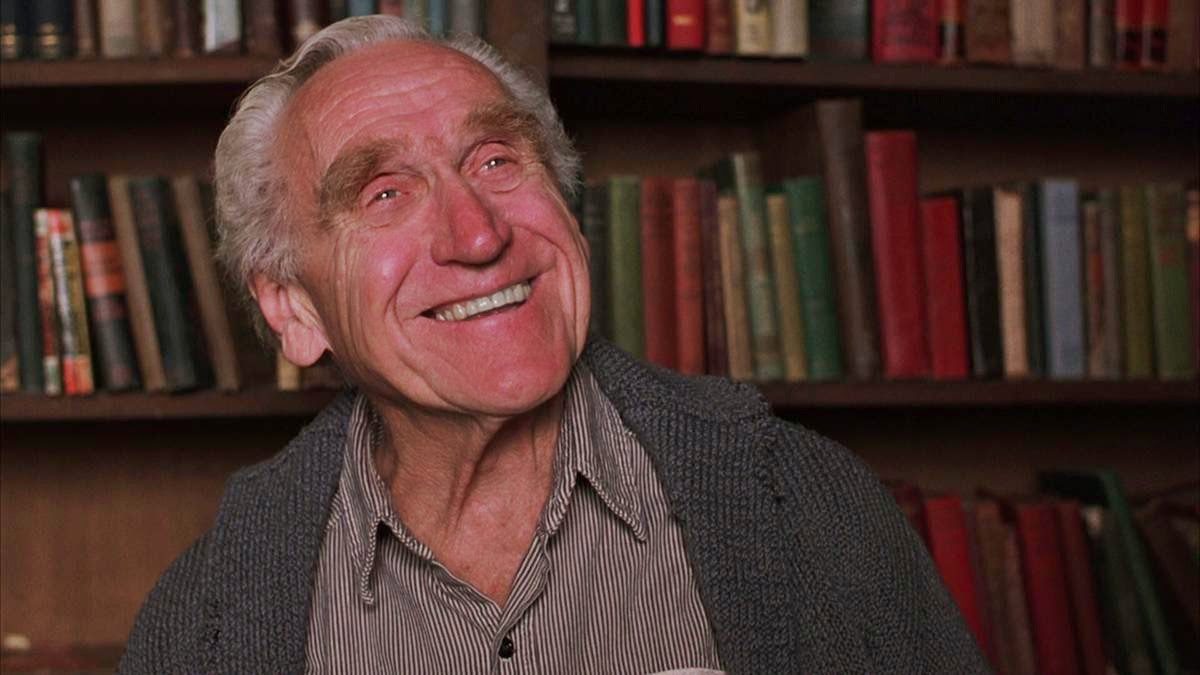

|

| Brooks from The Shawshank Redemption: a character who reinforces the crucial role that books play in prisons. |

The library? Gone… sealed off, brick-by-brick. We’ll have us a little book barbecue in the yard. They’ll see the flames for miles. We’ll dance around it like wild Injuns! You understand me? Catching my drift?… Or am I being obtuse?

Books have long been at the centre of the prison system, for reasons of entertainment, education and transformation. Anyone who has read a book and felt changed as a result can relate to this. Therefore, perhaps it could only be a lack of reading on behalf of the decision makers and prison boards that could lead to such a rule being put in place.

This quote by Tolstoy, written over a century ago in Resurrection, worryingly seems as relevant today as it did upon publication:

‘Where’s the sense in using prison for a man who has already become corrupted by idleness or bad example, and keeping him in conditions of guaranteed or enforced idleness, rubbing shoulders with other men even more corrupt than he is?’

Like more of the same? Subscribe to the Tolstoy Therapy Newsletter and receive a round-up of the week’s articles every Sunday to enjoy with your coffee. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more from me

- Retreat into my new book, Your Life in Bloom: Finding Your Path and Your Courage, Grounded in the Wisdom of Nature.

- I'm also the author of Mountain Song: A Journey to Finding Quiet in the Swiss Alps, a book about my time living alone by the mountains.

- If you love books, are feeling a little lost right now, and would love some gentle comfort and guidance, join The Sanctuary, my seven-day course to rebalance your life.